From 1928 through 1956 Yuma was a popular destination for “quickie” marriages for California couples. California was one of several states to pass a “Gin Marriage” law aimed at preventing hasty, alcohol-impaired marital decisions. In July 1927 the California legislature enacted a three-day waiting period for couples once they applied for their marriage license. And in 1939 California added a pre-marital medical examination requirement. Since Arizona had neither of these restrictions, Yuma–by virtue of its border location–quickly became the “Gretna Green of the West.” (The original Gretna Green, a border village in Scotland, had become a marriage haven in the same manner when England tightened its marriage laws in the 1750s.) As I discussed in an earlier article, Earl Freeman, Yuma’s renowned “marrying judge,” estimated that he married 26,000 couples during his 1926-1936 tenure as Justice of the Peace. During these years Freeman had had a near monopoly on the marriage business, but after his retirement, wedding chapels began popping up along 1st Street–Yuma’s “Chapel Row”–and a colorful, competitive marriage industry was born. One of the most unique and impressive players in this enterprise was the Reverend James Coleman.

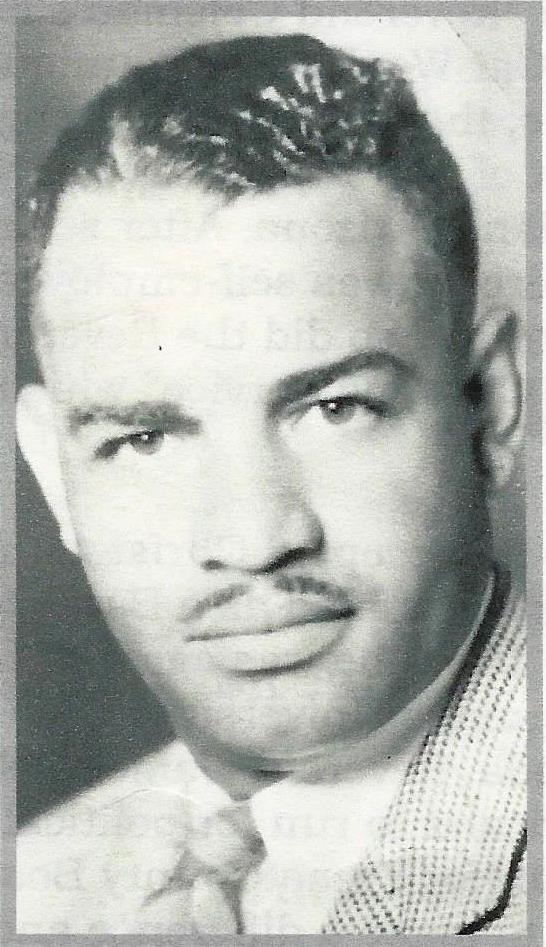

James and Lucille Coleman were both born in 1919–James in Louisiana and Lucille in Arkansas. The Colemans moved to Yuma around 1937, and, with the exception of a brief residence in Los Angeles and James’ two years of Army service at the end of World War II, they resided in the Yuma area for the rest of their lives. Although James did not possess a higher education degree, he was ordained as a Baptist minister as a young man. He had been unable to achieve his goal of becoming an Army chaplain, but he served several years as a chaplain for the American Legion during his 50-year membership in the organization. Rev. Coleman was never head pastor of a congregation, but he assisted at local churches, including Yuma’s Second Baptist Church.

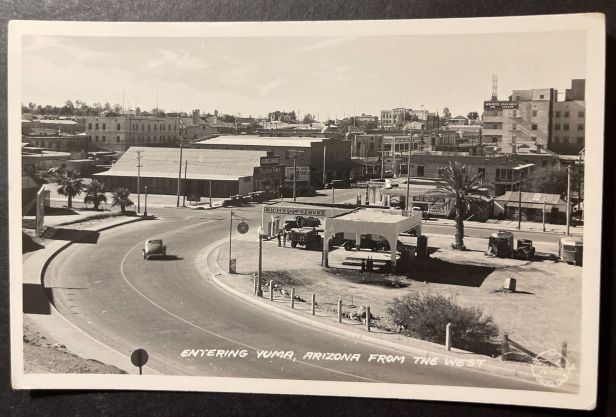

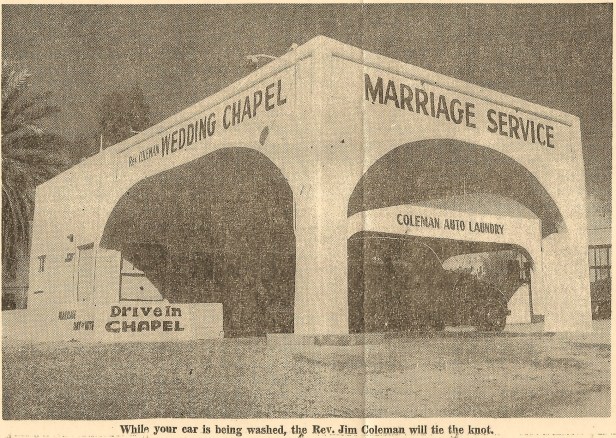

Prior to opening his wedding chapel in early 1948, James Coleman had operated a car wash (“auto laundry”) and auto engine steam cleaning business. He intended to stay in that business when he purchased the gas station pictured in the above photo. His was a prime location since it was the first landmark that motorists from California would see as they entered Yuma on Highway 80 over the Ocean to Ocean Bridge rounding the bend onto Yuma’s 1st Street. Justice of the Peace R.H. Lutes had converted the second gas station in the photo into an after hours wedding chapel a few years earlier. It didn’t take Rev. Coleman long to realize that with his location–and his ordained pastor status–that he was meant to join Yuma’s thriving marriage industry.

near the entrance of Yuma’s Gateway Park

In a 1990 Valentine’s Day profile in the Yuma Daily Sun, Rev. Coleman described the intense competition and “hustling” for couples that went on among Yuma’s various wedding chapels, particularly as couples arrived at the downtown bus and train stations: “ ‘A man could make a good living doing that. I paid as much as $7 for a couple. They were everywhere trying to hustle couples. It was quite an unusual deal in a way, but it was a business,’ said a chuckling Coleman.” Free transportation was offered by most chapels in order to prevent rival “hustlers” from diverting customers to another chapel.

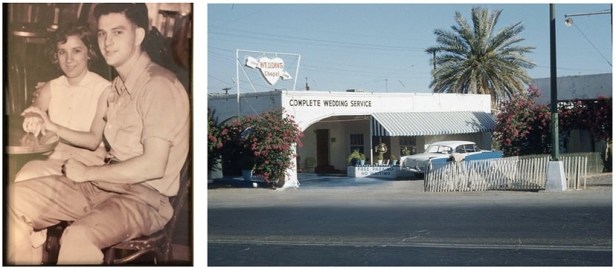

Mary Lou & Harold Mellina–Married by Rev. Coleman 6-2-51

On April 17, 2017 librarian Laurie Boone and I had the pleasure of conducting an impromptu interview with Mary Lou Mellina, a delightful 85-year-old woman who had been married by Rev. James Coleman 65 years earlier at the Drive-In Wedding Chapel. Mary Lou, a lifelong resident of Galveston, Texas, was in Yuma with one of her daughters in search of the site of her June 2, 1951 marriage to her high school sweetheart, Harold Mellina, who at the time of their wedding was a U.S. Navy Seaman Apprentice stationed in San Diego. Here are a few of Mary Lou’s quite vivid recollections:

- Well, he had it all set up for me to come to San Diego. Then he had it set up where his buddy would act like he was my father for them to call from Yuma. My daughter, who’s an attorney, said ‘Mom, you’re not actually legally married!’ [Harold was 20, which under Arizona law required parental consent for males. Mary Lou and Harold remained married for 60 years until Harold’s 2012 death.]

- I told my family that I was coming to see my aunt. I got on the bus and rode for 2 days and 3 nights or something like that from Galveston Island, got off the bus—he was waiting for me—got back on the bus and rode to Yuma.

- You know, we didn’t have anybody. It was just he and I, so Rev. Coleman had the cleaning lady—very nice—and some guy be our witnesses.

- I know when we got on the bus to go back to San Diego somebody on the bus—I don’t know if it was the driver—got up and told everybody that this young couple just got married!

Although James Coleman would later tell amusing anecdotes about his wedding chapel experiences, it is clear that he often had to endure unjust disadvantages and demeaning treatment due to the color of his skin. The November 1948 issue of Ebony magazine included a profile of Rev. Coleman that addressed the reactions he received from prospective couples at his chapel: “The majority tell him in a nice way that they prefer a minister of their own race to perform the ceremony. Very few are abusive.” In the article Coleman states, “I try to treat everyone alike. White, yellow, brown or black, we’ve all got one God, one Father.”

The Ebony article came out during the first year of Rev. Coleman’s wedding chapel operations. He later came up with a strategy to keep some of the “uncomfortable” couples from walking away–he hired a white and a Hispanic minister to marry couples who had such “preferences.”

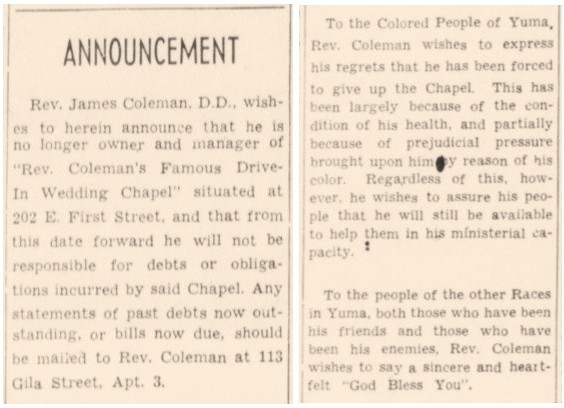

The above announcement from Rev. Coleman was much more than a legal notice stating that he was no longer the owner of the Drive In Chapel; it was a frank, emotional explanation of his being “forced to give up the Chapel” due to health concerns and to the “prejudicial pressure brought upon him by reason of his color.”

After selling the Drive In Wedding Chapel, the Colemans stayed active with their civic and religious groups, and they undertook several Yuma-area business ventures. James Coleman continued to offer an automotive steam cleaning service from the Coleman residence. From 1958-1960 James and Lucille managed the Agua Caliente Springs health resort located north of Sentinel. The couple expanded their residence into apartments in the 1960s, creating Coleman’s Downtown Lodge. And Rev. Coleman continued conducting marriages, funerals and other ministerial duties upon request.

The Colemans had long associations with Yuma’s NAACP chapter. Lucille held NAACP leadership roles, including Youth Council advisor. In the 1950s she wrote a “Yuma News” column for the Arizona Sun newspaper, a Phoenix publication, as well as serving as president of the Carver Elementary School PTA. James was interested in Yuma’s civic affairs and ran for political office in 1966, 1968, 1970, and 1971. He came close to winning a seat on the City Council in 1970, losing in a run-off election by only 21 votes.

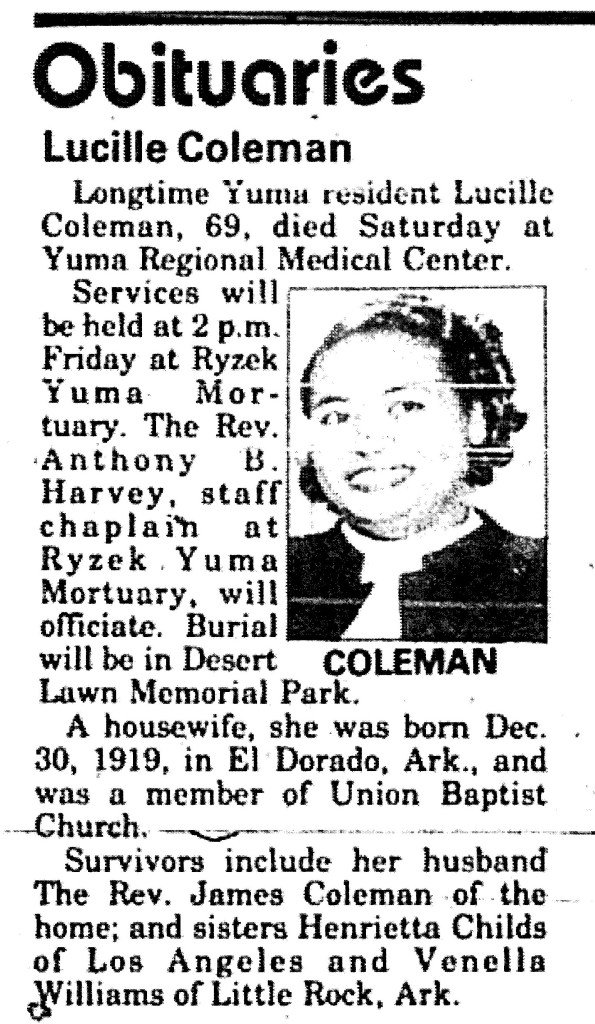

Lucille Coleman died February 25, 1989 at the age of 69. Rev. James Coleman died August 18, 2004 at the age of 84. While best remembered for the Drive-In Wedding Chapel, the Colemans spent nearly all of their adult lives in Yuma, making positive contributions to the community’s religious life, youth welfare, political and social causes, and much more.

Epilogue: Rev. Charles Cady and Yuma’s Famous Drive In Wedding Chapel

Rev. Coleman sold his chapel in 1954 to Rev. Charles Cady, a retired Baptist minister, who dubbed his new business “Yuma’s Famous Drive In Wedding Chapel.” The most “famous” wedding conducted by Rev. Cady was that of Aldous Huxley and Laura Archera.

A year after the death of his first wife, Maria, famed writer Aldous Huxley posed this question to former concert violinist Laura Archera: “Do you think it might be amusing to drive to Yuma and get married at the Drive-In?” Huxley had been fascinated by the Drive-In Wedding Chapel on a previous trip through Yuma, so on March 19, 1956 the couple eloped from Los Angeles to Yuma in Huxley’s Cadillac. Rev. Charles Cady married Aldous Huxley and Laura Archera after having an employee accompany them to City Hall to obtain a marriage license. Laura had changed into a new “lovely canary yellow suit” with the assistance of the dressing room attendant who also served as one of the couple’s witnesses. The groom was 61 and the bride was 40 on their wedding day. Sadly, their happy marriage was not a long one. Aldous Huxley died on November 22, 1963–the day President Kennedy was assassinated.

Celebrity weddings in Yuma, which seemed to be an almost daily occurrence in the 1930s, were uncommon by 1956. (The previous year’s big wedding saw B-movie actress Maria McDonald marry the 4th of her 7 husbands, “shoe magnate” Harry Karl.) And by the end of 1956 Yuma’s marriage business had effectively ended due to Arizona’s new marriage law requiring a pre-marital blood test. The one surviving chapel was (and is) the Lutes Wedding Chapel which in 1956 moved to its current location at 500 W. 1st St.

After closing Yuma’s Famous Drive-In Wedding Chapel at the end of 1956, Rev. Charles Cady remained in the wedding chapel business for another 20 years, first at the Little Chapel Around the Corner in Las Vegas, and then at the storefront Abbey Wedding Chapel in downtown Los Angeles. His L.A. chapel was only a block from the courthouse, and his ads promised 5-minute weddings for couples possessing the necessary paperwork. Déjà vu!