This month’s article is not about Yuma history, but the topic is of special interest to me since one of the orphans “given away” in Lindsborg, Kansas on June 28, 1912 was an ancestor of mine. After providing a brief summary of the orphan train “placing out” system, I will share a few details about the day Lindsborg hosted an exhibition of orphan train children.

Between 1854 and 1929 approximately 200,000 orphans and abandoned children were transported by train from New York and other Eastern cities to small towns in rural America, primarily in the Midwest. The children were put on display in community auditoriums for inspection by potential new families. The placing out system for these children–utilizing what came to be called Orphan Trains–was a compassionate, but flawed, response to a crisis of urban poverty and child neglect.

In the late 19th century, urban centers like New York City were plagued with an alarming number of children living on the street or in overcrowded orphanages. Since government did not yet play a major role in addressing social problems, it was up to religious and charitable organizations to fill the void. The orphan train movement was born from two such organizations: the Children’s Aid Society and the New York Foundling Hospital.

Children’s Aid Society—founded 1853

Rev. Charles Loring Brace (1826-1890) was a Congregationalist minister who headed the Children’s Aid Society for nearly 40 years. He witnessed firsthand the cruel impact of poverty, overcrowding and homelessness on New York City’s children. He strongly advocated the placement of orphaned and abandoned children in homes rather than institutions. It was Brace’s romantic faith in the benefits of rural living that led the Children’s Aid Society to uproot urban New York children and send them half-way across the country to live on Midwestern farms.

“The best of all Asylums for the outcast child is the farmer’s home.” —Charles Loring Brace

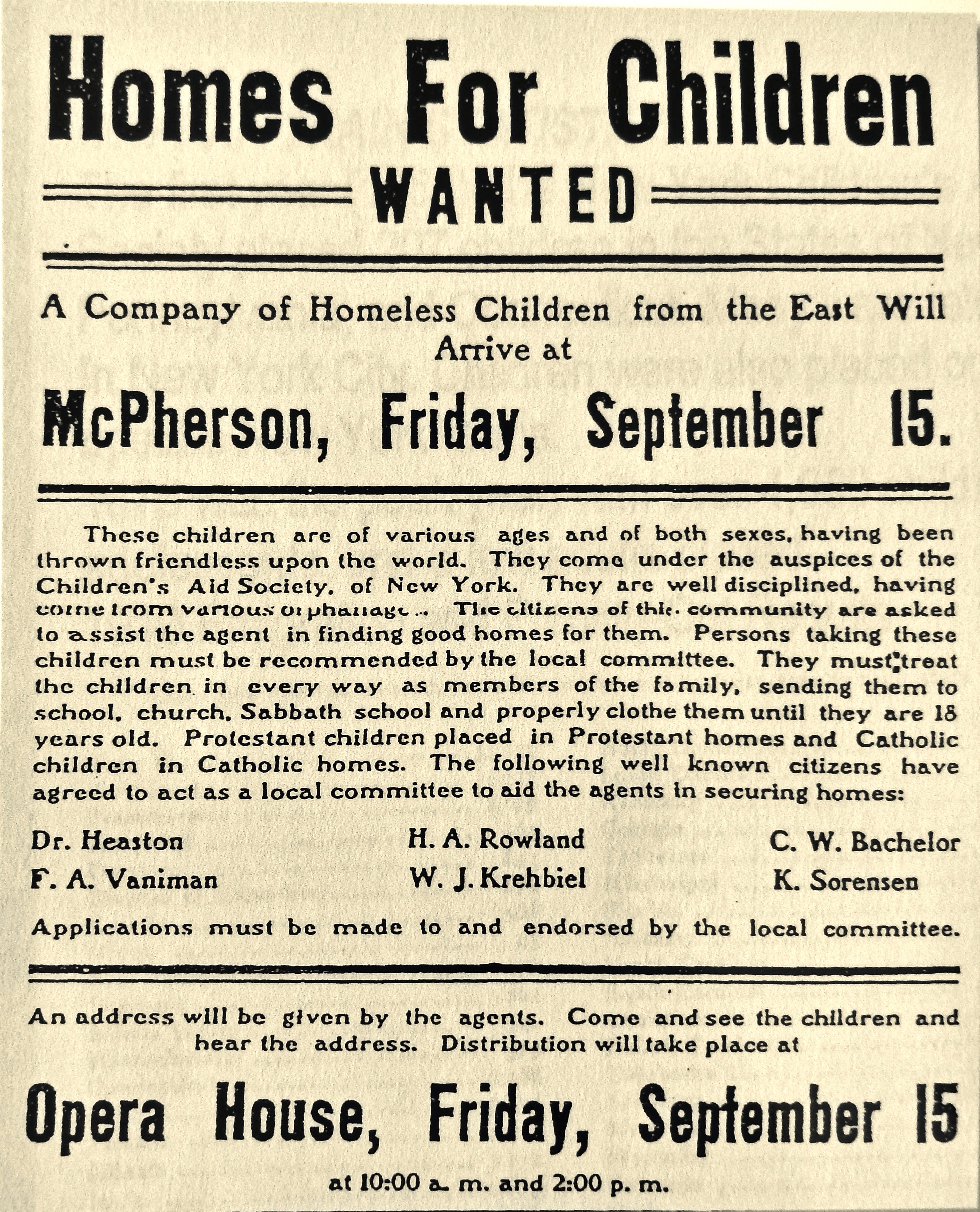

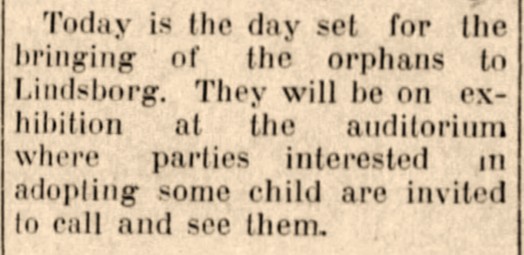

Over time the placing out procedures became well-defined. Small rural communities located on major railroad routes were contacted so that dates and public venues could be arranged. Newspaper ads and posters were provided to alert the local populations of the coming orphan trains. Each community was asked to form a selection committee, while placing agents tried to provide oversight by making follow-up visits once the children were placed in new homes. But in reality, the program was dependent on the good faith of the participating families.

New York Foundling Hospital, 1869–

The New York Foundling Hospital employed a different method of placing children than the Children’s Aid Society. Children were essentially pre-ordered and then delivered by train to the requesting families. Since so many infants were abandoned or given up at the Foundling Hospital, it was sometimes necessary to schedule “baby trains” full of youngsters such as those in the photo. As a Catholic organization, the Foundling Hospital strove to place Catholic children with Catholic families. Local priests and nuns took on similar roles to those of the Children’s Aid Society’s screening committees.

Success Stories / Criticisms

Defenders of the orphan trains have often pointed to “success stories” such as these former orphan train riders to argue for the overall effectiveness of the program:

Anna Fuchs, who came to McPherson, Kansas on an orphan train in 1924, considered herself a success story, as she explained in a 1979 interview: “The happy, well-adjusted ones like me have been swallowed up by society. I wanted our side to be heard, too. And I wanted to pay tribute to the people who opened their homes and made it possible for a child like me to get a second chance.”

Anna Fuchs, shown here with adoptive mother, Jennie Bengstrom, lived her later years in nearby Lindsborg, Kansas. The National Orphan Train Complex has more about Anna’s remarkable life.

Critics have called the orphan train system a “failed social experiment” with some of the strongest condemnation directed at the separation of siblings that frequently occurred when the children were placed with new families. Orphan Train Rider by Andrea Warren tells the powerful story of Lee Nailling who was blessed with a loving new family in Texas, but who also had to bear the pain of losing contact with his brothers until late in life. After the Nailling boys’ mother died, their biological father in New York felt compelled to commit his sons to the care of the Children’s Aid Society. Lee regretted never seeing his father again, but, according to Andrea Warren, it was the Society’s strategy to create totally new lives for the children: “Once a child left on a train, neither parent nor child knew how to find each other.”

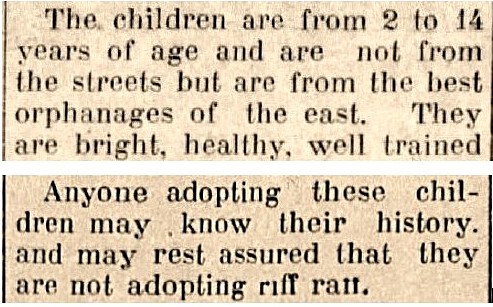

Children or commodities?

These clippings are from orphan train promotional announcements. In fairness, the Children’s Aid Society also stated, “. . . under no circumstances will a child be placed with people who wish chore boys or kitchen drudges.” But the labor shortage on midwestern farms did lead some families to select those children who appeared most capable of providing manual labor. Since a majority of the children were not legally adopted–most, in fact, had at least one living parent–the system was primarily an early foster care program. A sad result was that many of the participants had unstable childhoods lacking a sense of security, belonging and love.

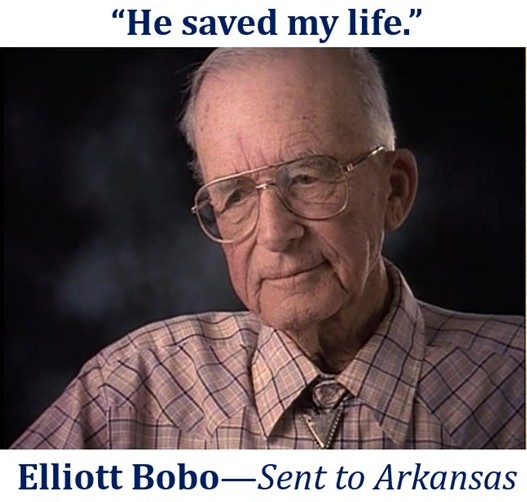

“The Orphan Trains,” a 1995 PBS documentary remains a valuable resource since it includes emotional, bittersweet interviews with some of the last generation of surviving riders who have since passed on. The following audio clips are taken from this documentary which is currently available for streaming from the library’s Kanopy service.

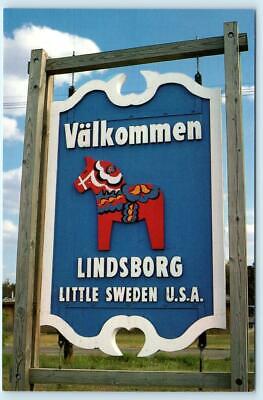

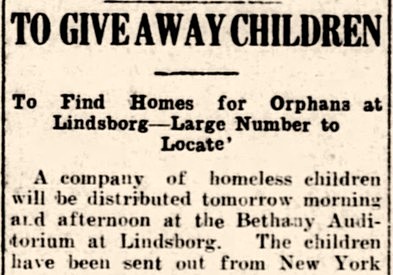

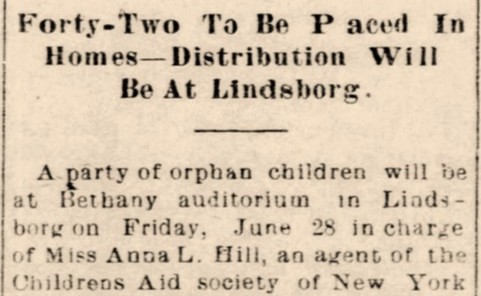

Lindsborg, Kansas—June 28, 1912

Throughout my lifetime, Lindsborg, Kansas has been like a second hometown for me, since both of my parents and many of my relatives were from the Lindsborg area. I mention this because on June 28, 1912, an orphan train came to Lindsborg from New York, and an ancestor of mine was among the children who were put on display and “given away” to willing Lindsborg families.

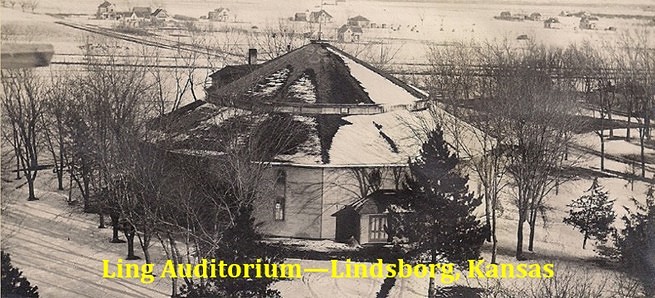

Bethany College’s Ling Auditorium–site of an orphan train “exhibition” on Friday June 28, 1912.

One of the children “on exhibition” at the Lindsborg auditorium was a 4-year old boy named George. My great-granduncle Charley Train–yes, his last name was Train–and wife Marie selected George and formally adopted him into their family. George Train died at age 84 in 1993. He had maintained a farm outside Lindsborg, while raising three children with his wife Agnes.

Legacies

Numerous factors have been suggested to explain the end of the orphan trains in 1929. State and federal agencies began taking a more active role in monitoring the welfare of children and families. Several states passed legislation which placed restrictions on the “importation” of children from other states. The interstate placing out of children gave way to more local forms of foster care which allowed for better oversight with a greater likelihood of keeping families together. By the end of the 75-year orphan train era, the United States had been dramatically transformed, and what was once seen as a benevolent answer to a desperate crisis was no longer sustainable or socially acceptable.

Even as adults, many orphan train riders were reluctant to talk about their experiences. Fortunately, as genealogy gained popularity, more research was directed at the orphan train movement, and numerous orphan train riders were successfully reunited with lost siblings and other relatives. Orphan train museums were established to preserve the history of the movement and to celebrate the lives of those involved. Many of the participants of orphan train reunions noted a sense of shared community and respect that allowed them to talk openly for the first time about their struggles as orphan train children. Today’s reunions consist of descendants of orphan train riders. These participants express pride in the resilience and courage of their orphan train relatives. They also share a mission to keep alive the stories of the orphan train riders.

Recommended Reading

The Andrea Warren titles shown here were written for young readers, but they offer poignant personal accounts that adults will also appreciate. Marilyn Irvin Holt’s book is a more scholarly examination of the orphan trains, and the author also served as a consultant for an informative documentary produced by the Smoky Hills [Kansas] PBS network: